|

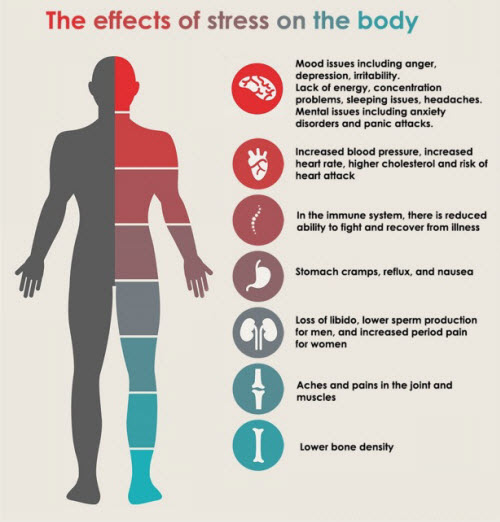

| Image credit – Executive Medicine |

The research was led by Dr. Justin Xavier Moor, an epidemiologist at the Medical College of Georgia and Georgia Cancer Center.

The study analyzed the effects of stress on cancer risk using data collected from 41,000 people who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1988 and 2019.

The results were published in the Sept. 2022 journal SSM Population Health.

The research team analyzed the NHANES data for the level of internal and external stressors faced by participants throughout their lives, including age, social and economic demographics, race, sex, and poverty-to-income ratio.

The stress level called allostatic load, was determined by body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and C-reactive protein, a measure of inflammation. The participants were categorized by allostatic load, low, medium or high. That data was then cross-referenced with the National Death Index maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics.

Without adjusting for any variables, the researchers found that those with a high allostatic load were 2.4 times more likely to die from cancer than those with low allostatic loads. When they looked at age they found that people of the same age with a high allostatic load had a 28 percent higher risk of dying of cancer than those with a low allostatic load.

When they looked at sociodemographic factors, such as sex, race, education, those with a high allostatic load had a 21 percent increase compared to low allostatic load.

Looking at race alone, however, yielded indeterminate results because the sample sizes were too small, for example among the 41,000 people studied, there were 11,000 non-Hispanic Black people, which meant too few cancer deaths to draw statistically meaningful results.

However, based on the researchers' earlier work, they had found that Black and Latino adults have an increased risk of high allostatic load when compared with their white counterparts.

Moore believes that difference can be attributed to structural racism — things like difficulty navigating better educational opportunities or fair and equitable home loans could over a lifetime raise a person's allostatic load.

“If you’re born into an environment where your opportunities are much different than your white male counterparts, for example being a Black female, your life course trajectory involves dealing with more adversity,” he says.

“As a response to external stressors, your body releases a stress hormone called cortisol, and then once the stress is over, these levels should go back down,” Moore said in a press release. “However, if you have chronic, ongoing psychosocial stressors that never allow you to ‘come down,’ then that can cause wear and tear on your body at a biological level.”

The research team analyzed the NHANES data for the level of internal and external stressors faced by participants throughout their lives, including age, social and economic demographics, race, sex, and poverty-to-income ratio.

The stress level called allostatic load, was determined by body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and C-reactive protein, a measure of inflammation. The participants were categorized by allostatic load, low, medium or high. That data was then cross-referenced with the National Death Index maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics.

Without adjusting for any variables, the researchers found that those with a high allostatic load were 2.4 times more likely to die from cancer than those with low allostatic loads. When they looked at age they found that people of the same age with a high allostatic load had a 28 percent higher risk of dying of cancer than those with a low allostatic load.

When they looked at sociodemographic factors, such as sex, race, education, those with a high allostatic load had a 21 percent increase compared to low allostatic load.

Looking at race alone, however, yielded indeterminate results because the sample sizes were too small, for example among the 41,000 people studied, there were 11,000 non-Hispanic Black people, which meant too few cancer deaths to draw statistically meaningful results.

“If you’re born into an environment where your opportunities are much different than your white male counterparts, for example being a Black female, your life course trajectory involves dealing with more adversity,” he says.

Sources: Augusta University Health News and SSM Population Health

No comments:

Post a Comment